Whooshkaa Studios: “Listeners are advised this podcast contains coarse language and adult themes, and is not suitable for younger ears.”

KATH POTTER: And they lit it, and I said to Liz, “Oh, my God. What are we going to do now?” And she said, “We’re going, Kath. Come on, we’re going.” And we got to the car, and the next minute, boom!

MATTHEW CONDON:So you heard the…

KATH POTTER: Oh, shit yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: You saw it?

KATH POTTER: I can still hear that. And I saw the flames, and she said to me, “What were you saying before?” I said, “Shut up, we’re going.” And I started to shake uncontrollably. The voice you just heard is that of Kath Potter.

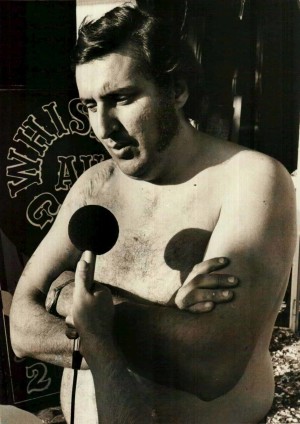

She was at the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub in Brisbane on the night of March 8, 1973, when it was firebombed. Fifteen people lost their lives.

All were dead within minutes from carbon monoxide poisoning. None were burned. As the smoke first billowed into the club, the lights flickered then failed, throwing the club into blackness.

Another patron in the club, Hunter Nichol, was convinced he was about to meet his maker.

HUNTER NICHOL: I honestly, as I said, I honestly and totally and 100% to this day, believe that night I was going to die. And I, just before I got to that window and the fresh air came in, I was on the point of collapse. And I remember thinking, God, mom and dad’s going to be…if I’d died this way. I remember thinking that. And then the fresh air hit me.

MATTHEW CONDON: You were resigned to death?

HUNTER NICHOL: I’d resigned to the fact that I was dying and I saw a white light.

MATTHEW CONDON: You did?

HUNTER NICHOL: I did see a white light. Sounds stupid. I could see … Whether I was on the point of collapse, mind taken over, and I was on the point of collapse, I don’t know, but I honestly and totally utterly believed I was on the point of dying. And staff member Donna Phillips remembers that night with terrifying clarity.

DONNA PHILLIPS: We heard a woman scream and we heard glass shattering. I’d forgotten previously, but it was another thing that I’d remembered was standing near that back door and looking back thinking, well, how can we help these people? Then with the shower, the sound of shattering glass, it was oh, maybe it’s too dangerous. I’ve come forward to the fence and hopped off.

MATTHEW CONDON: You heard someone screaming inside?

DONNA PHILLIPS: Yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: Once you got over the fence, you went across Amelia street and you sat on the footpath?

DONNA PHILLIPS: On the footpath with my feet in the gutter

MATTHEW CONDON: You were facing the club at that point?

DONNA PHILLIPS: Yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: You remember seeing it on fire?

DONNA PHILLIPS: Yes. Oh yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: Was it was a vicious fire.

DONNA PHILLIPS: I don’t, I’m pausing. Why am I pausing? Yes. In the club there were windows along the wall facing St Paul’s Terrace, but all were covered in decorative curtains. It didn’t matter. An inquest would find that the winding mechanisms on all those windows had previously been removed, and the windows riveted shut. A fire-resistant exit door had closed and was unable to be opened from the inside. Most bodies were found in an alcove next to that door.

It was a mixed crowd that evening. Of the 50 revellers, three girls were out on a hen’s night, and amongst the drinkers and dancers was a truck driver, the manager of a local suburban public pool, a pub owner from country Queensland, telephonists, a woman who worked in the canteen at the nearby Roma Street railway station, two members of the Military Police and two Queensland police constables.

The club itself had a reputation as a “last chance saloon”. Rumours lingered that prostitutes worked out of the Whiskey, and that hoods and crims held up the bar there. It had an air of danger about it.

It didn’t have the fancy atmosphere of Chequers, for example, at the top end of town in Elizabeth Street. The decor was chintzy. It strove for class, but was a hood’s idea of posh. As the old saying goes - you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. This was Fortitude Valley, after all. Yet it still attracted popular musical acts.

Kath believes she saw the killers lighting the fire at the front entrance. Hunter had friends perish and only made it out alive by seconds.

Donna saw a workmate with his shirt on fire, but she escaped, and has been haunted by that moment all her life.

Before Port Arthur, the Whiskey Au Go Go stood as Australia’s worst mass murder.

But what does all this have to do with Vince?

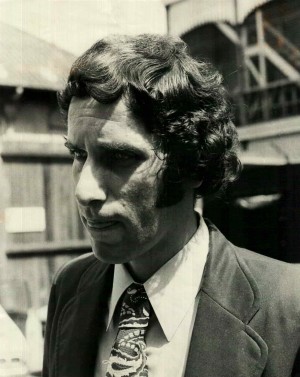

He claimed he was in Sydney at the time of the fire, but there is evidence that shows he was in fact Brisbane. One criminal told police that witnesses saw Vince “skulking” outside the club before the fire. Notorious NSW detective Roger Rogerson, who flew up from Sydney to help investigate the Whiskey in 1973, told a journalist decades later that a man named “Vince” threw a molotov cocktail into the club that night.

So what was true? What was fact and what was myth?

How could a mass murder occur in sleepy old Brisbane?

And most importantly, who was behind this infamous crime?

Logic tells us, it had to be someone who enjoyed the rush of fire, explosives and weapons. Someone who didn’t think twice about setting alight a club full of people, knowing many would die. Someone who knew that business was just business, no matter what the collateral damage.

That someone would have to have been a psychopath.

From Whooshkaa Studios, I’m Matthew Condon and this is Ghost Gate Road. In this episode, we will take you to the heart of one of Australia’s most horrific mass killings, and explain how the inferno led to the slaughter of an innocent mother and her children.

Audio footage from people close to O’Dempsey’s crimes, with Ghost Gate Road theme music throughout.

NEWS READER: People tried frantically to escape, Smashing through windows

Recent news report: what Barbara McCulkin knew about WAGG probably cost her life and her daughters

BRIAN BOLTON: now look you stupid bastard, whether you’re commissioner or not you’ll bloody well listen to me because people are going to die pal.

WITNESS: I could hear people screaming and you know, glass was breaking

FIRE FIGHTER: for me it was certainly more death than i’d seen in my career in the fire service

BRIAN BOLTON: after all they’re all mass bloody murders we all know that

NEWS REPORTER: until Port Arthur, Australia’s worst mass murder

Archival audio of news reader

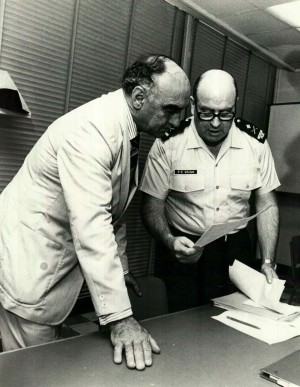

“The man who was tragically right was Brian Bolton. One of the old brigade of crime reporters in this country. A battered band of brothers who, see all evil, hear all evil and know all evil. Bolton is as colourful as some of the characters he writes about, he’s got battle scars, a tattoo and a nickname that’s becoming a legend…up here they call him The Eagle.”

Brian Bolton was a legend in the newspaper game.

The sort of hard-drinking, hard-working, chain-smoking reporter you might find in the pages of a potboiler detective novel.

They called him The Eagle because of the large tattoo of the apex predator he had on his arm. Inked by none other than the dodgy tattooist Billy Phillips, the drug dealer and stolen goods fence we met earlier in this story.

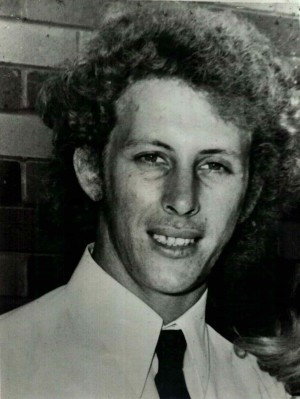

As for The Eagle, he wrote about crime. And he had a lot of informants. One was the Brisbane-born criminal psychopath John Andrew Stewart. We’ve talked about him earlier - the lunatic with the movie-star good looks who built his reputation on stabbing a man when he was a teenager. And, like Vince he was extremely violent and had been in and out of mental wards.

He was also a graduate of Westbrook.

It’s where he met The Eagle. The two - journalist and criminal - began a long association. Stuart tipped off Bolton about the underworld. Bolton mythologised Stuart in print as some sort of crazed young modern-day Ned Kelly.

Bolton’s son, Mark, had been eyewitness to his father’s rollercoaster life as a journo, filled as it was with dodgy characters and crooks and bent cops, much of it awash with grog.

With The Eagle, there was never a dull moment.

Mark, who still lives in Brisbane, told me about the beginning of The Eagle’s friendship with Stuart.

MATTHEW CONDON: So, yeah. Tell me how your dad first met John Andrew Stuart.

MARK BOLTON: Okay. I don’t know the full story I must admit, except for the fact that dad started at a newspaper called The Down Star in Toowoomba. And he heard about the Westbrook school thing, whatever you call it … The Westbrook Home. And again, looking into what was going on at Westbrook. And he met John Andrew Stuart through that. So the Westbrook Farm Home for Boys - that nursery for future gangsters - rears its ugly head again.

The Eagle would move to Brisbane and soon become the top crime reporter for the Sunday Sun newspaper. Its office was in the heart of Fortitude Valley, embedded in the suburb’s grubby bars and greasy spoon restaurants and illegal brothels and casinos.

When you stepped out of the Sunday Sun Building, you were in the heart of Brisbane’s Sin City.

Bolton was every inch the shambolic tabloid crime journalist, belting out stories on his typewriter in an atmosphere of booze and hard news.

This is Bolton describing his job. It comes from a documentary made years ago about his life:

Archive Documentary with Brian Bolton

BRIAN BOLTON: You’ve got to be prepared to be rung at any minute of the day and leap out of bed and go anywhere…to meet possibly the scum of the earth, the shit that knocks around this country, the drug pushers, the peddlers, the murderers, the rapists…you’ve got to be prepared to meet these people and deal with them in their own ground…alternatively you’ve got to be prepared at any stage to rip down to a quiet pub somewhere and deal with a bloody rough copper who mightn’t like you personally but he might like your style and he’ll ring you up and say, ‘Look, pal, I’ve got something for you, meet me at such and such a place at such and such a time’, and it might be bloody four o’clock in the morning but you get there, because what you’re doing is producing something for a few cents that is going to tell the people of this country what the hell is going on around them and they deserve to know this.

In early 1973 Brisbane was a city of fires.

There was the blaze at Alice’s restaurant in Fortitude Valley. Then Chequers nightclub. And then Torino’s.

It is worth asking the question - did the perpetrators of Torino’s go on to firebomb the Whiskey?

We know Clockwork Orange gang member Peter Hall confessed to the Torino’s arson attack, as you heard in the last episode.

Peter told me he and the gang had nothing to do with the Whiskey, but they were worried enough about being implicated after Torino’s to get out of town.

MATTHEW CONDON: Okay, so that was a successful job. And then, what, 11 days later?

PETER: Sorry, Matt. What was that?

MATTHEW CONDON: 11 days later the Whiskey Au Go Go goes up.

PETER: Yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: Where were you when you heard that news?

PETER: We were north of (inaudible) the time when we found out.

MATTHEW CONDON: So the day of the fire itself, was it daylight or-

PETER: No, it was nighttime.

MATTHEW CONDON: So the early hours of the morning?

PETER: Yeah, we were, doing a few break and enters and ah next thing it’s come over the news, so that was it. We just got off the streets real quick thinking what if they connect them both together and they start looking at us? That was, yeah, pretty toey for a little while there. Then in early 1973, The Eagle got a hot tip from his old mate John Andrew Stuart. Sydney gangsters wanted to muscle in on Brisbane’s restaurant and nightclub scene. They were prepared to use deadly force.

It was a big story. Bolton trusted Stuart, despite his friend’s criminal background and mental instability.

And Stuart was connected. He was friends with some of the Clockwork Orange boys. He knew Billy McCulkin, and was a frequent visitor to Dorchester Street. Some nights he stayed over.

Was his tale of a Sydney gang takeover true? Well there’d been a small fire at a nightclub called Chequers in February, followed by the blast at Torino’s. We now know Torino’s was organised by Vince and Billy McCulkin.

But Stuart was warning of a nightclub full of people being bombed. There was going to be loss of life.

Why did nobody take Stuart, and Bolton’s wild stories of Sydney gangsters set to storm the Brisbane club scene, seriously?

BRIAN BOLTON: “… this mass murder - the worst in Australia and as I understand from research the 4th worst in the world - should vever have been allowed to happen.

REPORTER: and Why do you say that

BRIAN BOLTON: Because there were so many warnings given by myself and other people by senior police.”

Especially the Queensland police.

And in another interview Bolton gave in the 70’s he said…

BRIAN BOLTON: “This is my own personal self recrimination, I think if i’d possibly if i’d gone up and hit him in the bloody mouth and said look you stupid bastard, whether you are Commissioner or not, you better bloody listen to me and put a bloke down there or people are goig to die, pal.” Remember, Stuart’s insane criminal life had been well-documented, particularly his psychological issues. He was branded both in the press and in the criminal underworld as a psychopath. He had been in and out of mental wards.

And Bolton? For all his talents as a magnet for seedy stories, he was a known alcoholic, and his newspaper, the Sunday Sun, did not shirk at sensationalism.

Could the pair be believed?

Just hours before the Whiskey firebombing, The Eagle had agreed to meet Stuart at his office at the Sunday Sun in Fortitude Valley. Stuart wanted to go to the nightclubs with Bolton and declare that if any of them were attacked, he had nothing to do with any extortion scheme. It reeked of Stuart setting up an elaborate alibi.

But Bolton didn’t make it to their meeting.

Mark remembers that night:

MATTHEW CONDON: And I understand Stuart turned up, but your dad didn’t. What happened to that meeting?

MARK BOLTON: Unfortunate timing. There was a journalist called Fred? Fraser who was quite mates with Dad at the time, or quite nights with Dad anytime. He went to England and they did a typical journalists' farewell at the airport to see eachother off , which entailed a lot of drinking. And so dad was a little bit past the sobriety by the time he got home, and that was sort of 4:00 or 5:00 o’clock from memory. And he sat down on the couch. I can see the living room, remember the atmosphere, everything. There was something just about that particular moment that won’t leave me. And he sat on the right hand side of the couch. And he said to us, “Wake me before you go to bed. I’ve got something important to do.” And so, you know, he’s full of grog, and you know, Dad could be a … How do I put it nicely? He could be an asshole when he was drunk. So we kind of left him there, and we didn’t wake him up. And that’s why he didn’t turn up. Stuart went ahead with his plan.

He dropped into the Whiskey for a moment at around 11pm and had a look around.

Then he went over to the nearby Flamingo Club, where he kept checking the time as it ticked towards early morning.

About 50 people were dancing and drinking inside the Whiskey Au Go Go on that Wednesday night, not busy by weekend standards.

Many had come to see one of Australia’s most popular live acts, the Delltones, who played a late set that evening.

The Delltones were a vocal group, formed in the late 1950s and fronted by the lanky Ian “Peewee” Wilson. Into the 1970s, they were still an extremely popular live act. They’d had a top five hit with their song Get A Little Dirt On Your Hands.

Delltones: Get A Little Dirt On Your Hands One of the band members was Brian Perkins. By fate, I met Brian just a few years ago in far northern NSW. He is now a real estate agent and works with his wife Janice selling properties in the Byron Bay region.

I had gone to inspect a property and Brian and I got talking. I told him I was writing about the Whiskey Au Go Go massacre in Brisbane in 1973. And he simply said to me: I was in a band called the Delltones and I was in the Whiskey that night.

As Brian tells the story.

BRIAN PERKINS: So, we did the show, everything was fine, we walked out and we said, I said to Noel, that the guy called Sep Martin and Bob Pierse were with us at the time, and we said, “We’re going now, you guys coming?” They said, “Oh no, we’ll stay back and have a couple of drinks.“And Peewee and I went downstairs and we just before we go, Peewee was driving and he said, “Uh, you think we should just check the boys?” And I said, “Well, maybe yeah I’ll just go back up,” ‘cause we’re just outside the club. I went back up and I said, “You going to come, you feel like coming now?” And they said, “Oh yeah, right-oh,” ‘cause I don’t think there was a lot happening after the show or didn’t seem to be. And anyway, they came with us and we heard the sirens on the way back.

MATTHEW CONDON : Oh my god, that’s incredible.

BRIAN PERKINS: And the smoke. That’s how quick it was, it must have been minutes after we left. About all I can say. God was on our side so to speak. Outside the Whiskey, as the Delltones were leaving, a young woman called Kath Potter was making a desperate phone call in a nearby phone box. She’d been in the Whiskey with a friend a minute earlier, waiting to meet her new boyfriend. He didn’t show up.

So just after 2am she telephoned Checquers nightclub, also run by the Whiskey owners, Ken and Brian Little, and tried to find her boyfriend, without luck.

Then while she was on the phone, she says she was looking towards the entrance to the Whiskey and saw something strange through the phone box glass.

MATTHEW CONDON: But somebody on that phone at Chequers

KATH POTTER: Said that, and I can’t tell you who it was because, until this day, I do not know.

MATTHEW CONDON: He said, to keep out of… get out of there.

KATH POTTER: He said, “Get out of there, now.” And I went, “Oh, why is that?” And just as I said that, the black car turned up, three men got out, they took a great big drum.

And I’m looking through the window of the telephone booth, and I’m going… And the guy was saying, “Are you there? Are you there?” I said, “I’m going. I’m going. Bye. Thank you”, and hung up. And then we stood… the pair of us were… I walked out and stood with her. We’re clinging hold of each other, and she’s going, “Holy shit, what’s happened?” I said, “I don’t know. Shut up, shut up, shut up.” Kath says she saw a large, long, black American-style sedan cruise up to the front of the entrance to the Whiskey, and three men get out. They were dressed in all-black, like terrorists. Two were of average height, and one was tall and thin.

KATH POTTER: No, I saw them get out the car, but I didn’t really look at the facial features. I just thought, “Oh, yeah, there’s three men getting out.” And didn’t think anything of it. Then when I saw them dragging the drum out of the backseat, and they’re carefully… They were pulling it out very carefully. And then the third one…the person who was in the back, got out, and he started it. The other two were helping. And then when they finally got it out, one of them went around to the back of the car, pulled it up, and got this white thing out. This white material, or shirt. Whatever the hell it was. And started ripping it, and then they stuffed it into the top of the drum.

MATTHEW CONDON: By this point, you’re panicking?

KATH POTTER: I wasn’t actually panicking at that point. I’m thinking, “What the hell is going on here?” And it wasn’t until they took… I started to… Because they’d gone, and Elizabeth and I are hanging onto each other for grim death. And we started to walk, because I thought, “We’re out of here”, because it was getting too late now to hang around. And we started to walk, but we stopped because we weren’t sure if they were coming back or not.

And we actually got to the corner where you could see what they were doing properly, and they put it into the entrance. Right in the entrance, but you could see some of it hanging outside. And I saw this guy was… It looked like a flame thrower, but I’m not saying it was a flame-thrower. It could’ve just been a long barbecue match. How the hell would I know?

MATTHEW CONDON: Hmm.

KATH POTTER: And they lit it, and I said to Liz, “Oh, my God. What are we going to do now?” And she said, “We’re going, Kath. Come on, we’re going.” And we got to the car, and the next minute, boom!

MATTHEW CONDON: So you heard the …

KATH POTTER: Oh, shit yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: You saw it?

KATH POTTER: I can still hear that. And I saw the flames, and she said to me, “What were you saying before?” I said, “Shut up, we’re going.” And I started to shake uncontrollably. She thought she was going to be sick.

We got in the car, and I don’t even remember driving home. To this day, I don’t remember driving home. Booms, burning and the ringing of an explosion Inside the club, Queensland police constable Hunter Nichol was enjoying a drink with his mates. One of them was military police officer Les Palethorpe. They’d heard the Delltones were playing at the Whiskey and wanted to see them live.

HUNTER NICHOL: Anyway, we walked in, went to sit at a table and Les saw another couple, a male and female, that he knew. Because he’s originally from the Redcliffe area, and they had grown up together, or went to school together. So he said, “Oh, come on, we’ll go and see them.” Words to that effect. So, walked over and Les introduced us to them. And the girl, well, both of them, invited us to sit at the table with them. There was a long trestle type table, it was right near the dance floor. So we joined them. Les got up to dance with his childhood friend, Fay Will. The band playing after the Delltones was a local outfit called Trinity. Hunter, the designated driver that night, sat on a single bourbon and coke.

Meanwhile, it was just another ordinary shift for staffer Donna Phillips.

Donna was 22, attractive and a part-time model. That night she started work at about seven o’clock.

MATTHEW CONDON: What was your role, your job that…

DONNA PHILLIPS: Well, look it varied. I was a waitress, I took drinks to the tables. I also served food. I remember thinking I was incredibly clever because I had this number of plates on this arm and plates here God I’m doing this thing so well. Then another stage as well to behind the bar, behind the table service bar down near the stage where I might’ve mixed cocktails and I was on the till for a while. Prior to 2am, management asked Donna to work the front counter of the club.

Then the telephone rang.

MATTHEW CONDON: What was, what’s your recollection of that phone call? You got a phone call to the club.

DONNA PHILLIPS: Simple phone call though, in the time that I was there, there’d been no other phone calls and I really don’t know what time it was. For me it would have been somewhere between 12 and two. The voice said is Brian Little There? I said, no, he’s not. Who can I say as calling, I might have even said, whom can I say I was calling? The voice said was no or anything like that it was just, the person just rang off. Then later on, when Brian Little came back to reception, I mentioned that to him then. It did seem a little bit unusual to me in those moments at that time that he gathered his partner and his brother and another man and said something like “we’re leaving now.” What caught me with that was that she didn’t necessarily seem to want to leave. She was a bit resistant or hesitant and said, well, why do we have to go? He didn’t say much at all and then they left. Not long after that, Donna went to the servery where her friend Decima Carroll gave her a drink of water.

It was about 2:08am.

Then all hell broke.

MATTHEW CONDON: What did you first notice? Can you remember?

DONNA PHILLIPS: Absolutely.

MATTHEW CONDON: You heard nothing?

DONNA PHILLIPS: No, I didn’t hear a firebomb type sound or whoosh of air or anything like that, but because I was standing facing the door facing right down…

MATTHEW CONDON: In line with the staircase?

DONNA PHILLIPS: In line with the door, staircase was further over, in line with the door. The fire has burst through that doorway, caught the curtains, but, at that stage, then the lights were starting to appear as though they were going out. I thought they were going out and other people did as well too, but if it’s correct, I’ve learned since that it was the smoke that made it appear as though the lights were flickering, but for me, if that was an electrical issue we’ll then you know, ouch.

MATTHEW CONDON: The smoke was billowing and it was black?

DONNA PHILLIPS: It was dark. It was dark. Yes. It was dark. Hunter Nichol’s recollection was different. The first thing that caught his attention was the sound of the fire.

HUNTER NICHOL: Well, we’re sitting there, next I just felt this big whoosh sort of thing, big blast of heat came in. And turned around, you just feel a terrific heat. Hit us first with this big whooshing sound. Turned around, we’re just completely enveloped in this real thick, pungent, stinking, thick smoke. Like you see with burning tires, diesel.

MATTHEW CONDON: A black?

HUNTER NICHOL: Real black thick. When I got out, I was covered in this black oily soot sort of stuff. On the whole of my body, clothes and everything.

MATTHEW CONDON: Did it like roll into the club?

HUNTER NICHOL: It just rolled in. Like you see these on TV out west with the big dust storms coming in. Except this is like a big lot of smoke just whooshed in. It didn’t roll in. It just blasted in. Whether the air conditioning was helping suck it in. But that’s like, it didn’t just roll in. It was a few seconds, less than a minute. We were completely enveloped in smoke. And everyone just scattered.

And I happened to look over towards where I ended up getting out. Which was a bar area, Chasing Black, which is on the opposite side to St. Paul’s Terrace. And next to the bar, I saw a door with a fire exit sign. And I saw a fire hose and a couple of people heading towards there.

MATTHEW CONDON: Did you hear anything?

HUNTER NICHOL: I saw people heading towards … No. I just heard this whooshing, roaring sound. It’s hard to describe, it was a roaring sound. Then I heard, in the smoke, it sounded like water. Well, I thought somebody must have activated the fire hose. I don’t know. I’m just making a supposition.

MATTHEW CONDON: What about other people, did you hear screaming?

HUNTER NICHOL: Oh yeah, there’s people just panic stricken. And luckily I was pretty fit in those days and reactions still pretty quick from being in the army. And I grabbed my handkerchief and soaked it in my drink and stuck it over my mouth and went down low. And try and get down below, because I knew smoke rises, try and get down where … because I couldn’t breathe. Donna froze with fear. By fate, she was near the club’s only emergency exit, near the kitchen. Two men asked her if she was coming, and she followed. She believes she was the third person out of the club after the fire struck.

MATTHEW CONDON: You were frozen?

DONNA PHILLIPS: Yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: Do you remember hearing anything? Smelling anything?

DONNA PHILLIPS: No smell, no significant sounds and I wasn’t overcome by smoke. I was just in the right place at the right time, essentially, just one of those interesting universal things I feel.

MATTHEW CONDON: Those men would have been pretty much one of the first out?

DONNA PHILLIPS: Well, I believe that they were the first two and that I was the third Once Donna got out, something happened to the exit door. It got stuck. Bodies were piling up against it.

As for Hunter, he’d lost contact with his friends in the thick smoke, but managed to drag a screaming young woman towards what he thought was the exit.

HUNTER NICHOL: And anyway, I called out to … Because Les and Fay and Bill, we just scattered. I called out, to come with me, come in this direction because that’s where I’d seen the fire escape, the sign. But they’d disappeared on me. I didn’t know, and it was just so thick, you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.And anyway, I started heading in that direction. I got on the dance floor heading in that direction. And there’s a girl there screaming on the … I did hear somebody call out fire at some stage, very early in the piece. But we’re just completely enveloped in smoke in under a minute. And this girl was there on the dance floor. She was just screaming out multiple times, “I don’t want to die.” “Will we all die.” She was just frozen in panic. And I’ve grabbed her and dragged her with me. And I was totally disoriented. I could hardly breathe. And I hit the bar area. And then I felt along there because I knew the door was there somewhere.

And I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face it was that bad. I fell on the bar area where I thought the door was. Luckily for me, the door I was aiming for, I missed that, that was the fire escape area where a lot of the bodies were found, at the entrance. Hunter found himself in the band changing rooms. He thought he saw people piling out of a small window.

HUNTER NICHOL: Yeah, Everything had gone. Everything had gone. I couldn’t see any fire escape sign, I couldn’t see nothing. We’re completely, totally enveloped in smoke. And couldn’t breathe.

Anyway, we got to this. And people were climbing through this hopper window. And I pushed a few people out. And then I pushed this girl I’d dragged with me out. Eventually I … I stood there getting a few puffs of fresh air coming in. That sort of revived me. Because at that stage, I honestly, to this day, completely and utterly believed I was going to die. I was on the point of collapse when this fresh air hit me. And don’t tell me that there’s no taste in air. It’s a very sweet taste. I could taste the air and it was sweet. And I got a few lungs full of air from what I could, enough to revive me. And I pushed her out and got out myself.

Hunter couldn’t know that he would never see Les, Bill or Fay alive again. Donna’s workmate Decima Carroll, a loving mother of three children, also didn’t make it out. Darcy Day, in the band Trinity, went back to fetch a saxophone, and died. As did ten others.

Emergency vehicles and police were quick on the scene.

The fire, largely at the front of the club, was extinguished within half an hour. And the bodies, near the back and untouched by fire, were soon removed. They were lined up and covered in white sheets on the footpath outside the Whiskey Au Go Go.

Firemen, ambulance officers and police at the scene had never seen anything like it. And they never would again in their careers.

Meanwhile, there was a banging on the door over at journalist Brian Bolton’s house in Ascot in Brisbane’s inner-north.

knocking on the door and tense music Bolton’s son Mark remembers the moment like it was yesterday.

MARK BOLTON: No. No, it was an eventful situation. And you got to remember, also we lived in a street called Monahan Street at Ascot, and it was very, very quiet on that street. At about … I don’t know the exact time, but about 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning, a journalist that was close friends with dad and a colleague called Brian Johnston lived at Eagle Junction. And Brian got a phone call to come around and get Dad. He’s knocked on the door at 3:00 and 3:30, 4:00, maybe, and he’s banging on the door and he’s saying, “Eagle, Eagle, the Whiskey is gone. The Whiskey is gone,” and it’s kind of ironic and a bit humorous, too, that the Johnstons had a dog called Whiskey, and Mom was wondering at that early hour of the morning, why Brian was coming around to tell us their dog had gone missing. That’s how sort of this whole thing started to unfold. Dad knew what Brian was talking about. So he goes out and I’d say, from that moment, he realized, “Oh shit.” so he immediately got dressed and Brian had took him to wherever he went next to. I guess, to the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub or to the police station. I’m not sure where they went, but that’s how we found out. We were woken up by this commotion. Later that morning, over in Dorchester Street, Barbara McCulkin, as was her habit, went a few doors down to the corner store to buy her morning newspaper.

The headlines screamed about the massacre at the Whiskey.

And Barbara was heard to say: “Oh my god, they actually did it.”

What did she mean? Who were they?

This was a tragedy on a scale that impacted dozens of families, hundreds of relatives, thousands of friends and acquaintances, and continues to have a painful ripple effect today.

I have met with the children of Whiskey victims and the agony of their loss is still just below the surface. They are quick to tears. The Whiskey is a horrific part of their everyday lives.

Kath, Donna and Hunter still agonise over it as if it happened yesterday. But so do many, many others. And all of them, bar none, still want answers.

They are all a part of a very unique, and sadly unimaginable, club. The survivors of the Whiskey Au Go Go.

So let’s take a look at what we know about this horrendous event so far.

The Whiskey massacre was a moment of absolute madness, a confusing and deadly collision of red herrings, false alibis, muddled memories, blatant lies, fate, police corruption, underworld greed, power and political manipulation.

The picture is as unclear today as it was at the dawn of March 8, 1973, when Australia woke to news of its worst mass murder.

A Brisbane journalist had been publishing stories claiming Sydney gangs were set to take over the Brisbane nightclub scene.

A well-known local gangster, John Andrew Stuart, warned authorities that a club, likely the Whiskey, was going to be torched as part of this extortion racket.

Just days before the Whiskey blew, Stuart had flown his best mate and fellow gangster James Finch out from the UK to Brisbane. Born in London, Finch was sent to Sydney as a child in the early 1950s with the Bernado’s charity for neglected and abused kids.

He crossed paths with Stuart in Long Bay Jail in Sydney in the early 1960s, and later in Grafton Jail in northern NSW. They became fast friends. So much so that Finch took the rap for the attempted murder of gunman Stewart John Regan.

Finch was later deported back to the UK, but when his mate John Andrew beckoned for his help with the Whiskey firebombing, and paid for his airfare, Finch came running.

In the lead up to the Whiskey, a couple of bars and clubs had been damaged by fires, and another, Torino’s, had been blown up. We now know Vince and Billy McCulkin had been behind that crime for insurance fraud.

In the week before the Whiskey fire, Sydney gangsters Lennie McPherson and Vince’s former employer, Paddles Anderson, are seen in the club. Did Stuart’s warnings about a Sydney takeover carry a grain of truth?

Just hours before the fire, Stuart, who went to painstaking lengths to establish an alibi for himself that night, appears briefly in the club then vanishes.

Whiskey employee Donna Phillips receives a phone call in the club just minutes before the fire, and owner Brian Little and his girlfriend swiftly depart.

Then a black car is seen cruising up to the club’s entrance, and three men get out and ignite two drums of petrol.

Within two to three minutes, 15 people are dead from asphyxiation.

Who masterminded this horrible crime? Was it planned down to the second, or was it a threat that accidentally got out of control and turned lethal?

After a decade going through files, and many hundreds of interviews with criminals, police, politicians, the victims’ children, firefighters who were there that night, eyewitnesses and members of the public, I still have no definitive answer to the riddle that is the Whiskey.

But I can make an educated guess.

The firebombing of the Whiskey was planned in advance as an insurance scam. Given Vince and McCulkin had planned a smaller-scale arson attack just eleven days earlier, it’s odds on they were also, at some level, a part of the torching of the Whiskey. Stuart and Finch were without doubt intrinsically involved. Some argue that the killing of fifteen people was unintended. That the job got out of control. I don’t believe this. Whoever set fire to those two fuel drums knew without doubt that there were people upstairs and that there would be loss of life.

As for the cover-up that followed involving Sydney gangsters, crooked Queensland police and politicians and a myriad of others, that is a complex story that may never be unpicked.

Not even Peter Hall, who took part in the burning of Torino’s, has any clear idea of what happened and who was behind the Whiskey after all these decades, though he too has his ideas.

PETER HALL: Still don’t know what was actually behind it. Whether city gangsters were mixed up in it, O’Dempsey was mixed up in it, the police involvement in it. Don’t know. I do think both police and Sydney gangsters were probably mixed up in it.

MATTHEW CONDON: In the Whiskey?

PETER HALL: Yeah. If he had meant to kill all those people.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

PETER HALL: I think it was an extortion gone wrong. As for Barbara, she was terrified.

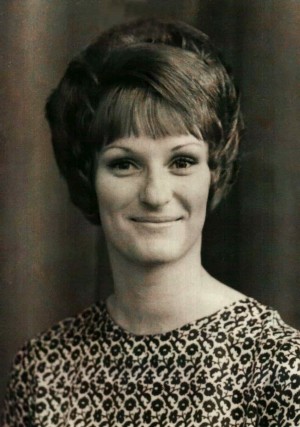

She fled Dorchester Street and farmed out her daughters, Vicki and Leanne, to separate friends.

Ellen Gilbert, Barbara’s friend who worked with her at the Milky Way Snack Bar in the city, would later tell police what happened:

ELLEN GILBERT (from police statements voiced by an actor): After the burning of the Whiskey Au Go Go nightclub in the Valley, Mrs McCulkin phoned me and asked me could she come to my solace and stay the night with me. She arrived at my home conveyed there by her husband, Billy McCulkin, and another person. After she arrived at my home she said she did not want to stay at home as she was very upset. She said something about the police and her house being bugged. I formed the opinion that Mrs McCulkin was very frightened and concerned for the safety of herself and her children and she had deliberately split them up. Just hours after the fire, police conducted a city-wide search and rounded up known criminals.

One of those was Billy McCulkin. He would later claim that he was questioned for hours before being released without charge.

But where was Vince?

Decades after the event a friend of Vince’s told me that he was in Sydney when the Whiskey went up. He heard the terrible news on the radio, she said.

But that’s a lie, because a trusted police source of mine only recently confirmed that Vince was nowhere near Sydney on the morning of the fire. He was in fact in Brisbane, and, like his mate McCulkin, he was caught up in the police sweep for likely suspects and brought into Fortitude Valley police station for questioning. He too was released without charge.

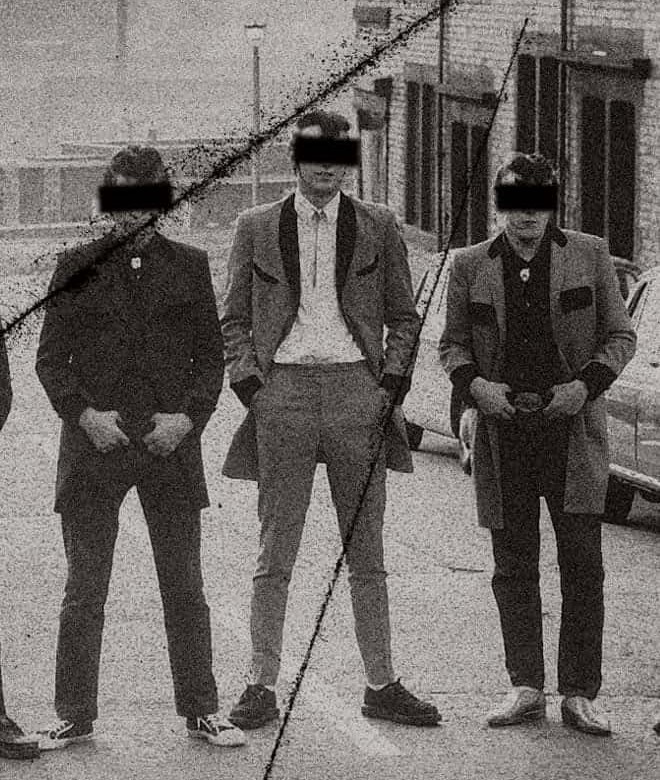

In the meantime, police were firmly focussing on John Andrew Stuart and his mate Finch as the prime suspects.

As for The Eagle, he was in shock. Had he predicted the tragic Whiskey story in his newspaper stories? Or had he provided Stuart with an alibi?

Mark Bolton remembers the impact on his father

MARK BOLTON: Yeah, look, I can’t put myself in his shoes, but I can empathize with the fact that the moment that Brian knocked on the door, the penny would have dropped. You know, “I should have been there.” And I think it’s only natural. I asked myself, “Would this have happened if I woke him?” I’m sure he was 10 times on top of that with, “What if I went?” And I can’t remember whether I ever heard him or he told me himself. That he was saying that all he had to do was stand at the front, you know, the front doors, because of the way that the fire bombing happened. His mind was, “I could have prevented it.” Therefore, I can only assume from that comment that he felt he could have done something about it. And he wore that. In the last couple of years, though, a few things have seriously troubled me about that night at the Whiskey Au Go Go.

There is Kath Potter’s sighting of three men dressed in black outside the club, sticking a wick into a drum full of fuel and lighting it, while police insisted there were only two suspects.

Kath gave a statement to police hours after the fire and told them what she saw. The black car. And three men.

They told her she was seeing things. There were only two men.

Five days later, Kath got home from work and had some visitors waiting for her.

KATH POTTER: So I get home from work and here were these two cars at the front of my house. They weren’t familiar to me. And I went inside and dad said, “Here she is now.” And they introduced themselves as two detectives and one policeman. I had gone down to Fortitude Valley police station, although it wasn’t called that then, and I had made this statement and they showed me the statement that I’d made. I said, yeah, that’s right. “No, it’s not. You’re lying.” I said, no, I’m not lying. I said, that’s exactly what I saw and I’ve told you what I saw and that’s what it is. “No, it’s not. You’ve lied. And we want you to change your statement.” I said, I’m not changing the statement, that’s what I saw. This is your signature? Yes, this is my signature. Why did police insist she change her statement?

Alarming, too, is an interview disgraced Sydney detective Roger Rogerson gave to a journalist just months before he was arrested for the murder of drug dealer Jamie Gao in 2014.

Rogerson was bragging about his role as an investigator in the Whiskey case. He was the big shot from Sydney, hand-picked and flown up to Brisbane to help crack the crime that shocked the nation.

Describing how he thought the fire was actually lit, he told the journalist:

ROGER ROGERSON (voiced by a voice artist): Finch was the one that did the job. The nightclub had a mezzanine. Vince went to the stairs at the back of the kitchen and threw a molotov cocktail in. Because it was downstairs the draft took it in and set the explosion rushing up into the club. Within seconds the whole place was on fire. There were 15 people in there. They were all killed. Let’s stop right there. Did he say Vince? That Vince O’Dempsey threw a molotov cocktail in?

Who was Vince?

Was this yet another case of Rogerson telling a tall tale to the media, as he had done so often and so effectively throughout his career?

Given he was 73 when he gave the interview, was this just an understandable senior’s moment?

But why would he pluck the name Vince out of thin air?

I needed to find out if he was referring to Vincent O’Dempsey, so I wrote to Rogerson in Sydney’s Long Bay Jail, where he is serving life.

I asked Rogerson about the quote in the newspaper story where he mentioned Vince.

“Dear Roger,” …I wrote… “there is no mention of Vince anywhere else in the story, not before or after this quote. And the story does not clarify who “Vince” is in your quote.

Roger, can you tell me who is the Vince you are referring to? The man who threw the Molotov cocktail in. Who is Vince?

If you could help with this”… I wrote… “you would be assisting in a correction of history that is way overdue, especially for the families of the Whiskey victims.”

Several weeks later, Rogerson replied.

ROGER ROGERSON Letter from Roger Rogerson voiced by an actor:

“To start with, none of that is my verbage, and to be quite truthful, it doesn’t make sense and does not fit in at all as to how the fire started. I have never heard of anyone called Vince having anything to do with either Stuart or Finch. I believe it was really a simple case. I think it gets down to this. When one psychopath gets with another psychopath you end up with mayhem. I think you are barking up the wrong tree.”

Roger then said he would enter no further correspondence on this subject.

Stuart and Finch were arrested and charged with the firebombing and murders.

Did Vince have a hand in the Whiskey?

Years later, a professional criminal and police informant, Robert John Griffiths, who had a reputation for being an habitual liar, signed a statutory declaration swearing that Vince was seen quote “skulking” outside the Whiskey on the night of the fire.

There is no doubt the Whiskey inspired Vince to embark on a murderous rampage the likes of which has never been seen in Australian criminal history.

But could he count those 15 Whiskey victims as notches on his belt?

Maybe we can finally answer that question.

Building tension with the Ghost Gate Road theme music Over in Dorchester Street, Barbara McCulkin and her two daughters, Vicki and Leanne, had just 10 months left to live.

END