Whooshkaa Studios: “Listeners are advised this podcast contains coarse language and adult themes, and is not suitable for younger ears.”

On location at Dorchester Street

MATTHEW CONDON: It’s a very moving thing to be here in Dorchester Street. It was where Barbara and the girls were last seen alive, by their friends the Gayton girls across the road. The house has not changed one iota, really, since that horrific night in ’74…and it is quite literally like it has frozen in time…so, let’s go and have a closer look at the McCulkin home.

For years, this has been Ground Zero in my investigation into the killer, Vince O’Dempsey.

I’ve lost count of the times I’ve come to this street and studied the shabby little workers’ cottage at Number 6, Dorchester Street, Highgate Hill. South Brisbane.

It was from here, on the night of Wednesday, January 16, 1974, that young mother Barbara McCulkin, and her two daughters, Vicki, who was 13, and Leanne, who was just 11, were taken by family friend Vince for a joyride in his snappy orange Valiant Charger.

A quick cruise around the city with Vince and his mate Shorty Dubois. What harm could that do? Barbara left the lights on in the house and her purse on the fridge. She was wearing her slippers.

She couldn’t know that she and the girls were about to be driven to their deaths.

It was here they were last seen alive.

What was going through Vince’s deranged mind that night? At the invitation of his mate, Billy McCulkin - Barbara’s husband - he had stayed in the house for six weeks after he was released from Boggo Road Jail in early 1971. He knew Barbara and the girls well. What possessed him to take them all the way to bushland outside Warwick and rape and slaughter them?

Why?

I had never been inside the house in Dorchester Street. I had pored over the old crime scene photographs of the interior- the cheap furniture, the aquarium, the make-up and perfume on Barbara’s dresser, the girls’ bedrooms with roller skates by the door and pictures of rock stars pinned to the walls.

I had always wanted to get in there, into that haunted house. To try and get a feel for the McCulkins’ last moments on earth. To stand where their killer, Vince, had stood.

And on my last visit, I noticed that the front door was open.

Matthew approaching the McCulkins house on Dorchester Street

HARRY: Hey.

MATTHEW CONDON: How are you?

HARRY: What’s up?

MATTHEW CONDON: My name’s Matt Condon, I’m a writer, and I’ve published a book on Vince O’Dempsey and the McCulkins case…

HARRY: Yep.

MATTHEW CONDON: And this is where the McCulkins lived…

HARRY: Yeah, I genuinely wondered when somebody was going to come and ask about it.

MATTHEW CONDON: Seriously.

HARRY: Yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: I live in Byron Bay, but I’ve come up to Brisbane to do some podcast stuff which I’m doing on Vince O’Dempsey, and I noticed the door open…and I wondered, should I try and take a look at the house.

HARRY: Yeah. Do you want to?

MATTHEW CONDON: That’d be fantastic.

HARRY: Come in.

MATTHEW CONDON: What was your name?

HARRY: Harry.

MATTHEW CONDON: Nice to meet you, how are you?

HARRY: Nice to meet you. I was interested in it, but I’ve never known anyone who really knew about it.

MATTHEW CONDON: Seriously? What do you want to know?

From Whooshkaa Studios, I’m Matthew Condon and this is Ghost Gate Road -

In this episode, Vince shifts from country town thug to a life of big city gangs, underworld heavies and entrenched police corruption.

Audio footage from people close to O’Dempsey’s crimes, with Ghost Gate Road theme music throughout.

GARY LAWRENCE: Believe me, they’re all scared of him mate. All the coppers were scared of him.

PETER HALL: His eyes stood out most, cold, black, icy-looking. I had hair in them days and it made the hair on the back of your neck stand up when I looked at him?

GARY LAWRENCE: He could tell a lie and believe me, you could have him there for five days and he would still remember the littlest of the lie he told. He remembers everything, mate.

JIM SLADE: without a doubt in my mind to get to be the very best detective, you had to have the very best informant

In the last week of December 1970 two prisoners inside Brisbane’s Boggo Road Jail were woken at 4am.

It was already warm, even at that hour, and the men washed up, had a cup of tea, dressed into civilian clothing, and were ordered to wait in the holding area.

Both were set to be released from jail after lengthy sentences.

One was Bob - that’s not his real name - who was 24, a car thief and rouseabout, and still bitter at having to spend almost five years in prison for a crime he says he did not commit. Wrong place, wrong time.

The other man was Vince . He was 32. He’d served five years for stealing a safe from a department store. And he was about to be set free.

I was put in touch with Bob through a good source. I was told Bob was a man of few words, and that the odds of him talking to me were next to zero.

Loose lips sink ships.

Bob had an extensive criminal history, and had been in and out of jail up and down Australia’s eatsern seaboard. And while he was cautious when I called, we ended up meeting for coffee in northern New South Wales, and he grew to trust me.

Then he started to open up about Vince, and the day they were sprung from jail - or as Bob calls it, “the boob” - on the same day in 1970.

BOB: Then we were walking up and down in the yard and there was this screw who was an arsehole called George Dale, He got a bit heavy-handed, he sort of roughed me up with his hand, the back of me suit coat, all this shit, you know… And he said, you’ll be back. I said I won’t be back voluntarily, I can tell you, I said not like you, you come here every day voluntarily and annoy people…when I’m brought here I’m brought here in chains. Vince thought that was funny.

BOB: Vince had a bit of a laugh and we were walking up and down after Dale stormed off, and he said, you know it’s a black day for society today. It’s a black day for society today.

Seven words that Bob has thought about now for exactly fifty years.

Bob and Vince had become friends in Boggo Road. Both were hard men. Both were career criminals. And here they were, about to step out into a new decade.

The sixties were dead and with new decade heralded a new life for Vince O’Dempsey.

Bob is an extraordinary storyteller. He’s witty. He has a thousand tales about a lost generation of Australian criminals.

And he will never forget what Vince told him in the holding yard in 1970.

MATTHEW CONDON: You said that great line to me…he came out a bright, shining monster…what do you think that stretch, that second stretch in Boggo Road for Vince…it was probably the worst possible think, literally for society, to put a psychopath like that in Boggo Road at that moment in his life when he’s going to come out as this total, fully-fledged psychopath.

BOB: Well he was one before he went there.

MATTHEW CONDON: What do you think Boggo Road did to him?

BOB: It makes you a bit harder and more determined to, you know, break the law….

MATTHEW CONDON: I’m just trying to get if Vince used the time to sharpen his ambitions, criminally.

BOB: He would have. He would have. He’d have been thinking how he could get a few hits in and Christ knows what.

It’s a black day for society today.

MATTHEW CONDON: What did you take that to mean, back then?

BOB: The program never worked. (LAUGHTER) That’s the best way I could describe it. He wasn’t going to get a job and settle down.

Large prison doors opening and the music swells At exactly 6am, Vince walked out the front gates of Boggo Road jail and was a free man.

A monster was on the loose.

On that morning Bob was met by his relatives outside the jail’s front gates and taken home. One of Vince’s brothers was waiting for him.

The records show, however, that Vince did not go home to Warwick – where he had a de facto wife, Margaret, and a five-year-old daughter, Sharon , waiting - but to a house at 6 Dorchester Street at Highgate Hill, less than two kilometers from Boggo Road.

Why didn’t he go home straight away to his loved ones? He’d been locked up with hard men for years. Did he hesitate at the family responsibilities that awaited him?

The small wooden workers’ cottage in Dorchester Street–the house I visited at the beginning of this episode – was rented by Billy McCulkin and his family.

Billy, a local petty gangster, thug and alcoholic, had stolen the safe from the Fortitude Valley department store in 1966 with Vince. Someone dobbed them into the police. Vince was jailed. Billy served a month on remand.

But they were clearly close enough for Billy to invite Vince, when he got out of jail, to stay for several weeks at his home until Vince got back on his feet.

Billy was married to Barbara, then in her late 20s. They had two young daughters, Vicki and Leanne.

Did Billy know that he had a sexual predator under his roof for those six weeks? Billy would later tell police that Vince was a model lodger. That he was quiet and went to bed early.

The other visitors to the house were not so well behaved. Dorchester Street became a bit of a clubhouse for Billy’s criminal mates. And they were an eclectic crew.

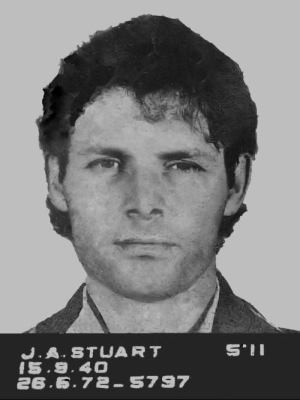

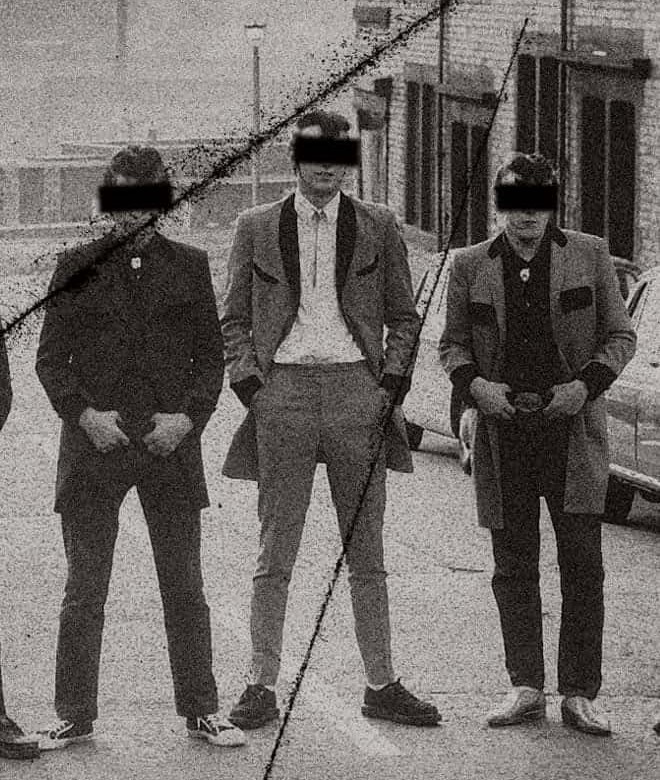

ominous, paparazzi camera clicks and stabbing sounds. They included John Andrew Stuart, a wild and violent Westbrook graduate with movie star good looks who’d built his reputation on stabbing a man when he was just a teenager.

ominous, tattoo gun and money/coins bag There was Billy Phillips, a tattoist, stolen goods fence and weapons dealer who’d ink women in exchange for sex.

Then there was the Clockwork Orange Gang, named after the classic Stanley Kubrick film about a psychopath, Alex, and his gang of droogs who went on crime sprees where they raped and pillaged.

In the film, Alex wears a bowler hat.

The local Clockwork gangers, however, all came from the rough, tough suburb of Chermside in Brisbane’s inner-north.

The gang members were obsessed with American cars, particularly Studebakers, and had a couple in loud colours. At one stage they also owned a hearse which they called the party car.

boxing hits and ends with a big punch There was Tommy “Clockwork Orange” Hamilton - a feisty redhead and aspiring boxer who sometimes affected the bowler hat of his delinquent movie hero.

Keith “Jimmy” Meredith - he sported a monstrous afro and was nicknamed after his twin, guitar hero Jimmy Hendrix.

Peter Hall - the prankster.

car revs with a skid and drives away And Gary “Shorty” Dubois - short, with long hair, a handlebar moustache, who had a passion for young girls and a mouse tattooed on his penis. He was obsessed with American cult killer Charles Manson.

Years later, Peter Hall told me about Shorty and the strange hold Vince had over him.

MATTHEW CONDON: I was wondering what it was, the relationship between Vince and Shorty. Shorty was never afraid of Vince?

PETER HALL: I think he idolized him.

MATTHEW CONDON: Really?

PETER HALL: Yeah, I think O’Dempsey had some sort of a spell over him. Shorty had a thing for that idiot over in America.

Shorty became obsessed with cult killer Manson. He grew a Manson-like handlebar moustache and read about his hero in news magazines in prison. Friends said when he read about Manson, he whooped in admiration.

MATTHEW CONDON: Oh, Charles Manson?

PETER HALL: Yeah. Shorty had a thing for him. Thought he was pretty smooth.

At Dorchester Street, crimes were planned.

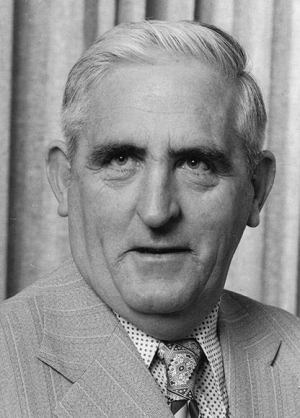

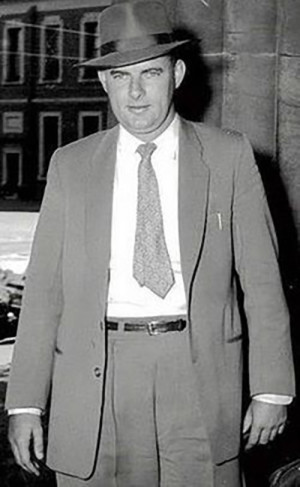

And Billy and his mates discussed at length their peculiar dance with the corrupt police of the day, mainly Detective Glendon Patrick Hallahan and Detective Tony Murphy. Both men were feared officers who, at a whim, could frame you for anything from murder to shoplifting, and fit you with a quote “present”, like a gun or drugs.

If you can’t beat them, the crooks reasoned, join them.

Hallahan was like Fagan, out of Charles Dickens’ famous novel about street urchin Oliver Twist, in control of his little band of Artful Dodgers.

MATTHEW CONDON: In the 60s was there a suggestion that … Was Hallahan in the background anywhere there?

PETER HALL: Yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: What was his role? What was he up to?

PETER HALL: We went to Hallahan, Tom spoke to him and he got in contact with him and said to him, “You’ll stay a detective sergeant for the rest of your career unless you help these boys and you’ll get to move up the food chain.” So yeah, they took money and charges dropped down to next to nothing and yeah, he did get to go up. He ended up an inspector.

Criminal Gary Lawrence, who we’ve already met - trust me, you’ll remember his voice when you hear it again - had countless run-ins with Hallahan and Murphy. He says both were extremely violent and corrupt to the core. While Murphy was the boss, Hallahan was often the muscle.

GARY LAWRENCE: That Tony Murphy, you know. when I went in for insulting the police think it was three months or something like that. Well when I got out… Them days when you were getting out and the police wanted to see you, they’d hold you in between gates, right? Well, him, Murphy and Hallahan picked me up and took me down underneath the Story Bridge and threatened to kill me and all that.

MATTHEW CONDON: Really?

GARY LAWRENCE: Yeah, “We don’t want people like you fucking bashing police”, and all that fucking stuff. And they threatened to kill me and everything. I tell you, well I shit myself.

MATTHEW CONDON: Do you think Tony Murphy was capable of murder?

GARY LAWRENCE: Fucking course he was. Fuck me dead. Mate believe me, they’re all scared of him mate. All the coppers were scared of him. He was one of the main movers in that thing they had going, and yet no one told on him. He sat there glaring on them, and not one. People didn’t start talking about Murphy until after he died.

Lawrence thought Hallahan was a thug. But that Murphy was pure evil.

GARY LAWRENCE: Hallahan. He was beyond, mate. He was a fucking terrible cunt. He was probably worse than Murphy, he was a sly bastard. He’d get other blokes to do his dirty work. He wanted a statement… he would get one of his cronies to take it. But he’d be there, calling the shots. Their name would be written on it so that you couldn’t get up and say, “ah, Murphy hated me”. But they’d say, “but he didn’t take the fucking record of interview”.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

GARY LAWRENCE: Fucking bullshit! He was behind every fucking word that went in that record. He was a sly bastard, mate. You picked him real, you know.

Mate, he had a photographic memory. That bloke, I’m telling you. That’s why he could fuck anybody. And when other cunts would fuck up, he would come back and fix it up, because his memory was… He could tell a lie and believe me, you could have him there for five days and he would still remember the littlest of the lie he told. But tell me that at the end he said he couldn’t remember, fucking bullshit. Fair dinkum, he remembers everything mate.

This was the deal in early 1971, with Vince out of jail.

Corrupt police like Murphy, Hallahan and their underlings controlled the crime. And the criminals played along, as best they could, to survive. You will hear a lot more about police corruption as we go along.

In the meantime, the Clockwork Orange Gang was cruising through Brisbane, looking for trouble.

MATTHEW CONDON: In the early ’70s, so Shorty’s out of jail, you’re all in Brisbane, you’re driving around in Studebakers, you’re doing a bit of break and enter, nothing too heavy, but just describe that world to me, if you can, Peter. But were you flatmating and bunking in together in various houses?

PETER HALL: We were at times, yeah, renting a house and all of us living in the house. And when something bad went down and we had to get out of the house and that, we’d split, go home to our parents' houses, and then once we’d got another house where to stay, we’d go and stay back there again, and yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: So you were a pretty close bunch of dudes at that period, obviously.

PETER HALL: Yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: And what did you like about Shorty? What was the good side to him that attracted you as a friend?

PETER HALL: Well, he was a good face to work with.

MATTHEW CONDON: Why was that?

PETER HALL: It was sort of we had each other’s backs at the time, back then. His joint was where we went and hung out. And yeah, it’s really hard to put something on it. We sort of liked doing the same things, like yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: I mean, you trusted him, obviously.

PETER HALL: Back then, yeah.

And the gang ramped up its illegal activities in the early 70s.

MATTHEW CONDON: And what sort of jobs would you do?

PETER HALL: It was just more or less random. We would go out during the day, see what’s about, like trucks, deliveries. You’d hoist from the back of the truck when the driver went inside during a delivery, you’d run up and grab a couple of cartons. It was just grab what you could, and if you saw something that was ripe to come back to that night, that was good. Like we’d see cigarette deliveries, and the supermarkets where you’d wait till they come back out, you’d just go in. And they used to just put the cartons, big boxes of cartons just over the chrome rails. Well, you’d just walk inside, just lean over and pick them up. Because we did it in front of everyone, no one took any notice of you. Yeah, so that sort of stuff, and we’d see where a big delivery and you’d go back that night and get round the alarm system, and they were pretty easy to get around in those days.

As for Vince, the lodger of Dorchester Street, he received a surprise visit from his de facto wife, Margaret. She was trying to understand why he hadn’t come home to Warwick.

So in late February, 1971, Vince went back to his hometown and tried to play the responsible husband and father.

And he even got a job. A job he was perfectly suited for. He was employed as a slaughter man on a poultry farm.

By a strange coincidence, the family of a colleague of mine when I worked at the Courier Mail Newspaper in Brisbane once owned a chicken factory in Warwick where Vince, fresh out of jail, took some work late in the summer of 1971. After following some leads I managed to find a woman who actually worked there at the same time as Vince. She told me…

Chicken farm and abattoir CHICKEN WORKER (voiced by an actor): She was built like a brick shithouse back then, when he got out. Vince would be in there in the smoko room eating his cake and chatting away. He was a very smart man. Very cluey. But he had terrible eyes. Scary blue eyes. They were chilling

They used to come off…all done by hand when he was there, we used to have a rotary plucker…they’d chop off their heads, it was pretty gruesome…they’d come onto a big stainless steel table and everyone would line up on both sides and you’d cut their feet off and cut their guts…then he used to catch the chooks…he was pretty quick tempered. He was quick tempered.

Vince’s period as a “square head”, or straight, law abiding citizen, didn’t last long. The poultry farm records show that he ceased employment on April 23, 1971. He’d managed nine weeks of gainful employment.

It was a mug’s game. He had bigger fish to fry. It was time to move back to the Big Smoke of Brisbane.

Vince, his de facto Margaret and their child, Sharon, moved into a rental in Harcourt Street in New Farm in Brisbane, abutting Fortitude Valley in the city’s inner-north-east with its brothels, illegal casinos, dive bars and rowdy pubs.

Vince needed some money coming in, so he called on his old mate Billy McCulkin, who secured him a job as bouncer and general dog’s body at a shonky mock auctions shop in Queen Street, the city.

auction and lots of people in a hall The mock auction was a con that stretched back to Victorian England. Punters would enter the auction room and bid for wrapped packages. Unaware of the contents, they might pay peanuts for something genuinely valuable, or good money from items that were worthless.

Usually, they did their money.

The scam, run by local horse racing identity and businessman Paul Meade, was financed by Sydney mob boss Frederick “Paddles” Anderson. Anderson supplied the auction goods. All stolen, and shipped up from New South Wales.

Vince, you might remember from a previous episode, did some work for Paddles in Sydney in 1965 before he was charged with carrying an unlicensed pistol.

Now, at the mock auction, Vince fitted right in.

He was connected again to the Sydney mob. And he could flex his muscle and indulge in his love of violence on the door of the mock auction.

Meade’s longtime assistant, and lover, Estelle Long, would later admit to police:

ESTELLE LONG (voiced by an actor): I had been in an on again off again relationship with Paul Meade for about 17 years prior to becoming involved with Billy McCulkin in 1973. I remember when I first learned who Vincent O’Dempsey was, I was warned by Paul Meade to stay away from him as he was a very dangerous man. I knew that Billy and O’Dempsey had known each other for many years…I remember hearing they did a safe job at Walton’s Brisbane’s main drag is more gentrified these days. Today, not far from the old auction house, is Tiffany’s, Louis Vuitton, and other elite shopping destinations.

But some places can’t shake their history.

Matthew on location

MATTHEW CONDON: So here we are outside 154…it was a part of the old Brisbane Arcade building, three levels which is still here…the Brisbane Arcade is still here…and the mock auction shop it appears is where there is now a Pandora jewellery store…. and it was right by that door at Pandora’s that Vince worked literally as a doorman and he would keep out undesirables, and he would keep out the police, he in fact had many witnessed stand up fights with O’Dempsey and interested members of the constabulary, and he kept them out…

But let’s go all the way back to 1971 for a moment. Through the auction, Vince had returned to working in the criminal underworld. And by complete chance, a young police constable by the name of Alan Marshall remembers Vince working in Queen Street. A few years later Marshall would be ordered to investigate Vince for the murder of the McCulkins.

He clearly recalls seeing Vince at 154 Queen Street.

MATTHEW CONDON: Those mock auctions, I mean Vince had been released from jail at the end of 1970. So they were ostensibly run by Paul Mead, and the material for the mock auctions actually came from the gangster Frederick “Paddles” Anderson in Sydney. So there was a connection in Sydney, with the underworld in Sydney. But O’Dempsey was working as a, well strong arm if you like.

ALAN MARSHALL: Yeah. I know he used to wrap stuff out in the back room. Yep. Because I found that out somewhere along the line. And I know that sometimes he’d go in and make him, a bodgy bid, probably just to bump the price and stuff up.

A young Peter Hall from the Clockwork Orange Gang also remembers Vince at the Mock Auctions. It was the first time Peter had ever laid eyes on him.

MATTHEW CONDON: And do you remember what Vince looked like. He was the bouncer at the door, right?

PETER HALL: Yeah, the scene that stood out most … He’s not all that tall. A reasonable build on him, but his eyes is what stood out the most and-

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah. Describe them to me, even the first time you met him. What struck you about them?

PETER HALL: Oh, cold, black, icy-looking. I had hair in them days and it made the hair on the back of your neck stand up when I looked at him.

MATTHEW CONDON: And were you aware that Vince was potentially a killer even at that point?

PETER HALL: Yeah, I knew he had a pretty bad reputation as far as hurting people, making them disappear. But it was sort of … Knew nothing for sure. Just sort of innuendos.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

PETER HALL: But as soon as I looked at him I thought, “Well, there’s a big chance that this is a bloke you can’t really trust or rely on.”

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah. I mean apart from the eyes, did he have a dangerous or menacing air about him, do you think?

PETER HALL: No, he didn’t speak or anything like that to sound dangerous. Just his eyes, when you looked at his eyes and you realized that he’s quite handy with his fists. And then yeah, then other stories came out later about the gun and how he preferred the knife and things like that, yeah.

Let’s just take stock here for a moment.

Vince has now had three stretches in jail. The first in the early 1960s for nearly kicking a police officer to death in Warwick. The second for carrying an illegal handgun in Sydney in 1965. And third, for stealing a safe in Brisbane in 1966.

He has a history of sexual assault.

He has already been involved in dealing drugs.

And Vince is a diagnosed psychopath.

He is living with his de facto wife Margaret and child in one of the seediest parts of Brisbane. And he is earning a quid working for criminal identities in both Brisbane and Sydney.

Vince’s gangster mates going back to the 1960s will always tell you that Vince had an almost pathological hatred of the police, or the squiggly tails as he used to call them. Hadn’t he nearly beaten one to death?

But that doesn’t tell the true story.

In fact, the reality is the opposite.

When Vince settled in Brisbane in 1971, he committed one of the great cardinal sins of the criminal underworld. He began secretly working for the police as an informant.

And he hooked up with not just any police officer, but none other than detective, Tony Murphy, a man both feared and admired. Murphy was widely known as a member of the corrupt Rat Pack, along with detectives Glen Hallahan and Terry Lewis.

All three had been mentored by corrupt former police commissioner Frank Bischof during the 1950s and 60s.

So here was Queensland’s top detective getting into bed with Queensland’s top criminal.

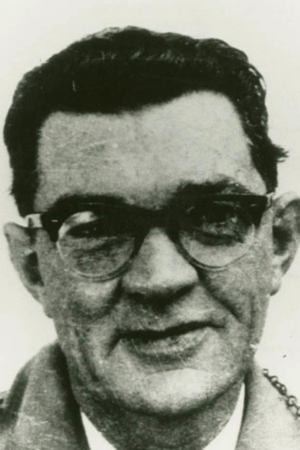

I asked former Queensland police intelligence officer and undercover operative, Jim Slade, who worked closely with Murphy for years, how Murphy’s unique partnership with O’Dempsey may have come about.

JIM SLADE: The only way for a detective to get up to the level of Glen Patrick Hallahan, Krahe, Roger Rogerson and Tony Murphy etc would be to start off very young, they would have well and truly known that their best tool to make them known firstly to their superiors, make the superiors look good in the face of politicians to be able to control crime, was to have a very, very good stable of informants. So they would have started early, and they would have been on the lookout for people like O’Dempsey, and they would have cultivated them right from square one, and as I’ve said before, it works both ways. The criminal would have sense it was an advantage to him, so without a doubt in my mind to get to be the very best detective, you had to have the very best informant.

MATTHEW CONDON: And that would mean the very best criminal of the day.

JIM SLADE: Without a doubt. And a criminal that was not only organising things but had already networked his criminal associates to be across what they were planning and what they were doing as well.

MATTHEW CONDON: So the mathematics is logical, isn’t it, the number one detective gets the number one criminal.

JIM SLADE: Yes. And of course he gets the number one kudos through the media and as I say his superiors right up to the political end of town.

MATTHEW CONDON: And what in exchange does a man like Vince O’Dempsey get by hooking up with a man like Tony Murphy?

JIM SLADE: So when he would have been working as an informant for Tony Murphy, we look at the stage in a business where the first thing that you’ve got to look out for is your competition…and wow, what better way to get rid of your competition but have a very, very good police officer in your back pocket, so to speak, and to be able to call on him and get him to get rid of your competition for you.

Brisbane was rife with police corruption. It was also home to a burgeoning prostitution industry, still disorganised, ad hoc, a cottage industry in the early 70s, before the big madams came up from Sydney and revolutionised the business in the Queensland capital a few years later.

But in 1971, the coppers needed an organising principle to make sure they received regular kickbacks. And that organising principle was Vince.

Warren “Wazza” McDonald worked for Vince for more than 20 years. He became known as Vince’s “apprentice”. And there was very little Vince didn’t confide in Wazza.

I met McDonald a few years ago and immediately enjoyed his company. He has a hilarious turn of phrase. A sharp memory. A big laugh.

And he remembers like it was yesterday Vince talking about those days in Brisbane in the early 1970s.

MATTHEW CONDON: Mate do you remember anything…Vince gets out in 1971 and his fortunes don’t start to really pick up until 1972 when I think he must’ve got on board with the coppers to manage the brothels.

WAZZA MCDONALD: Well mate he never had much money.

MATTHEW CONDON: But back in 71 he hooked up with Paul Meade, we know that.

WAZZA MCDONALD: Yes yes yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: And the mock auctions.

WAZZA MCDONALD: Yes.

MATTHEW CONDON: But that wouldn’t have earned him much.

WAZZA MCDONALD: No. Nah.

MATTHEW CONDON: But how did he survive?

WAZZA MCDONALD: Oh mate, look, being a tough guy. He’d get a hit here and there.

MATTHEW CONDON: A literal hit?

WAZZA MCDONALD: Yeah mate, there’d be terrible, there’d be terrible bloody unsolved murders in NSW that he was responsible for.

MATTHEW CONDON: And this is in the early 70s?

WAZZA MCDONALD: Yeah.

Then into 1972, Vince suddenly appears flush with cash. He buys a bright orange Valiant Charger – one of the most popular and eye-catching vehicles of its day.

He paid $4,500 for it.

The two-door, six-cylinder car was extremely popular in Australia in the early 1970s, helped by a string of television advertisements promoting the vehicle and its “masculine” chassis as sexy and an object of seduction and lust. The soft porn movie star Alvin Purple, played by the actor Graeme Blundell, featured in one of the ads in 1973, trailed by a gaggle of females hoping to get a lift with him in his new Charger.

The ads showed young women, men and even children crying out to the car and its drivers, “Hey Charger!” while gesturing a “V” peace sign with their hands. “Hey Charger” virtually entered the language.

Valiant Charger television advertisements.

“Hey Charger…

Hey Charger…

Hey Charger…

Hey Charger…

“The unbelievable can happen to you.”

Vince had even driven his distinctive car out to his hometown of Warwick on a few occasions to show it off. Everyone in Warwick knew about Vince’s hot car.

Next, he bought a part-share in a block of land in Warwick with his new boss, Paul Meade.

Where was the cash coming from?

Wazza has a pretty good idea.

WAZZA MCDONALD: He’d be getting a rake off the sheilas, you see, off of the molls.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yep. Yep. And this was when he was the king of the brothels in Brisbane.

WAZZA MCDONALD: Yes, he was the strong arm for the prostitutes.

MATTHEW CONDON: Where would he be getting his kickback from.

WAZZA MCDONALD: From the moles. See, everybody had to pay him. If you turned up on the corner and had a couple of molls, you’d get a fucking belting and he’d take your molls off you. Or if you went and did the right thing and asked permission, right oh, well you can have that corner, but you’ve got to give me a rake off.

Even at this early stage, however, Vince was tied up with corrupt police, especially Tony Murphy.

Peter Hall didn’t want to believe Vince had been a police informant. Only in recent years has he joined the dots.

MATTHEW CONDON: That’s right… It doesn’t make any sense that he could murder at will and yet never be charged with or taken to court to face those charges for decades. Logic asks, how does that happen? He had to have been protected.

PETER HALL: That’s it. There’s only one answer. He’s not that smart that he covered his tracks so well because there are a couple of witnesses with that bloke that they thought was in the dam.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

PETER HALL: He was caught stealing the car with O’Dempsey.

Matt: Yeah.

PETER HALL: Until you start thinking, how did he get away for all those years with what there’d been in between? Then the McCulkin’s disappeared. There was just no doubt left at all that he was, what you’d call, a protected species. And the reason why is because he was doing big favors for corrupt police.

Vince had committed the unthinkable. He went into business with corrupt police. It’s a secret he’s tried to keep to this day.

Only now have his criminal mates begun to air their suspicions.

Wazza, however, has no doubts.

MATTHEW CONDON: But did he mention any kickbacks to the cops? There must have been some.

WAZZA MCDONALD: I remember BLEEP saying he was paying Murphy.

MATTHEW CONDON: That Vince or BLEEP were paying Murphy?

WAZZA MCDONALD: Vince was paying Murphy. Because he said to Dad, don’t worry about Vince, the cunt, he pays fucking coppers. I’ve never paid a copper in my life, fucking BLEEP said. You know you can’t pay coppers. I don’t work with fucking coppers. He said Vince has.

MATTHEW CONDON: And he was paying Tony Murphy.

WAZZA MCDONALD: Murphy.

By early 1973, Vince was flying high.

He’d settled in Brisbane. He’d dumped Margaret, and his daughter, Sharon, and taken up with a new woman - prostitute and alcoholic by the name of Diane Pritchard.

He had his beloved Valiant Charger, and his fingers in several illicit pies.

And then a business opportunity came up.

Vince was asked to organise an arson attack on Torino’s, a restaurant in Fortitude Valley owned by the Ponticelli brothers, for insurance purposes. Vince jumped at the chance, and with Billy McCulkin, he planned the firebombing.

They asked the Clockwork Orange boys to do the dirty work.

This crime remained unsolved for almost forty-five years. Only recently did Peter Hall, one of the crew tapped to blow up Torino’s that night in February, 1973, confess to the arson.

MATTHEW CONDON: Can you tell me about the origins of the Torinos job.

PETER HALL: Oh, Torinos?

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

PETER HALL: Yeah…who contacted Shorty and Shorty came back and said this needs to be done for insurance reasons, and there’s 500 there for us.

MATTHEW CONDON: So you got the job offer for Torinos and that came via Vince through Shorty?

PETER HALL: Yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: And what, what the night was set and did you put much thought into how you were going to burn it?

PETER HALL: we just thought, oh we’ll get a couple of plastic containers and fill them up with petrol. And we drove around, had a look, everything was quiet and parked the car away, walked back, went around jamming the back door open. We went in and had a look around in there, We just sprayed petrol everywhere and that was pretty funny, left enough in one of the things to run a trail out the back door. And dropped a match in it, and instead of just catching fire like we thought it would, and the fumes didn’t go up. And as we ran around the front across the road, just blew the front of the building out.

MATTHEW CONDON: Oh, God.

PETER HALL: Just exploded. So, yeah.

MATTHEW CONDON: You could’ve done yourself some damage there.

PETER HALL: Could have. I thought, wow, if we didn’t do anything like that again that I can remember, but the fumes blew up…

The gang got out of there with their lives, and after the explosion they were pumped with adrenaline.

It was the biggest job of their criminal careers. Forget nicking electrical goods. This was fire and brimstone. This is what real gangsters did.

Back in Dorchester Street, Barbara knew in advance about the Torino’s job. How couldn’t she? Her husband and Vince had planned it in the family home.

Nobody was harmed in the blast. It was an insurance scam. And Billy got paid his share in cash.

But Barbara was also picking up plans for another firebombing. This time a nightclub in Fortitude Valley called the Whiskey Au Go Go, a late night dive in St Paul’s Terrace run by crooks and bash merchants.

How much did Barbara know? How could she have foreseen that eleven days after the Torino’s blast, someone would torch the Whiskey and within minutes lay claim to Australia’s worst mass murder?

PETER HALL: I do think both police and city gangsters were probably mixed up in it.

MATTHEW CONDON: In the Whiskey?

PETER HALL: Yeah. If he hadn’t meant to kill all those people.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

PETER HALL: I think it was an extortion attempt gone wrong.

MATTHEW CONDON: Yeah.

PETER HALL: But from what I’ve read about the carpet, stuff going up, the fumes, they maybe all died from the fumes. They reckon it only took a few minutes.

Ghost Gate Road theme music Fifteen dead in just minutes.

And after almost fifty years, big questions remain unanswered.

Did Barbara know enough about the Whiskey to have unwittingly signed her own death warrant? This innocent woman in her shabby cottage in Dorchester Street, trying to raise two kids, sewing their clothes, taking them to the local roller skating rink every weekend, doing absolutely everything in her power to give them a decent future.

And on that terrible night - March 8, 1973 - at 2:08am, when fire raced up the staircase of the nightclub and met its victims. Where was Vince O’Dempsey?

Where was Vince when the Whiskey blew?

END